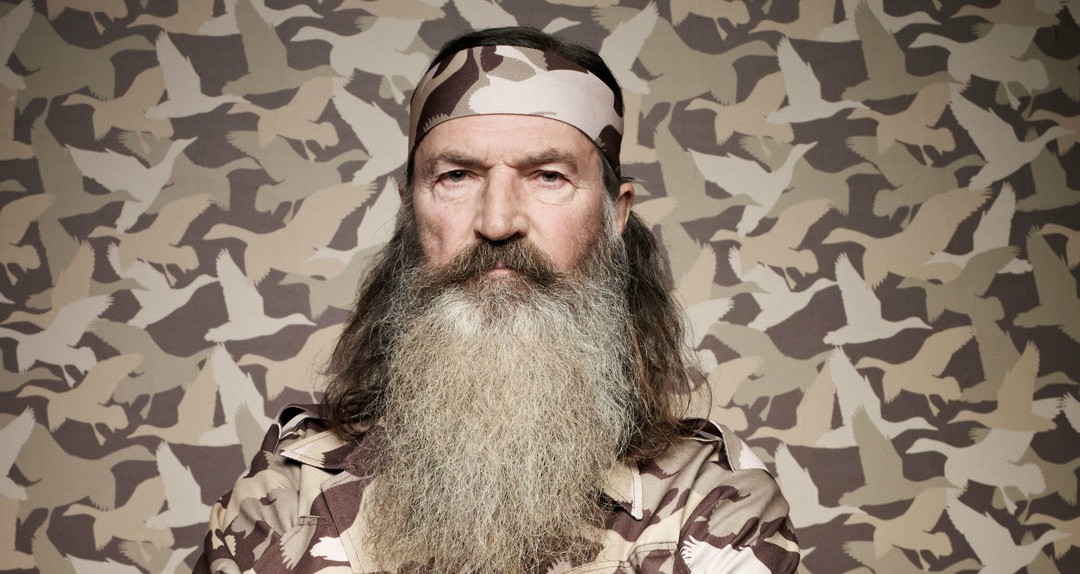

Why Gay Rights Proponents Should Support Duck Dynasty’s Phil Robertson

Whether you agree with Phil Robertson about homosexuality (click here and scroll half-way down to read the original comments he made) or you disagree, there is something troubling going on here, and it should alarm everyone, including gay rights proponents.

Whether you agree with Phil Robertson about homosexuality (click here and scroll half-way down to read the original comments he made) or you disagree, there is something troubling going on here, and it should alarm everyone, including gay rights proponents.

However, when I first wrote and published this article, I concluded that it was an issue of free speech, though not with the federal government, of course — as the feds have no hand in this Phil Robertson drama — but in regards to the laws that protect employees from being discriminated against or fired for their personal beliefs expressed outside “the office.” I’m of course referring to Title VII of the Civil Rights Acts.

However, this argument doesn’t exactly work either. Michael Lotfi at the Washington Times gives a few reasons why. But what it comes down to is this: Phil Robertson did not sue his employer for a violation of Title VII. If he doesn’t believe his rights under that Act have been violated, it’s a little hard for anyone else to make that claim.

And now that he’s been reinstated on the show, the argument that his Title VII rights were violated becomes an ever more moot point.

All of that being said, I still strongly believe that something troubling is happening in our culture. When I first wrote the article and warned that the loss of civil debate in society will eventually lead to the predicament that Martin Niemöller addressed, I was remembering people I met in college — radical activists, to be exact — who expressed their belief that Christians should be thrown in jail for uttering any belief contrary to their own about homosexuality. On the other hand, I’ve known gay rights supporters who were not only friendly towards Christians, but they stood up for Christians when others attacked their Bible-based beliefs with name-calling and personal insults. This latter group of people was more open to calm, thoughtful debate and discussion with those who had an opposite worldview.

However, that latter example has become rarer in our culture. Many of the public responses to Phil Robertson — the name-calling and ill-wishes towards him and his family — reminded me of the vengeful, angry activists I met in previous years.

It seems as if we can’t disagree with each other without personally insulting one another with name-calling and vitriol. There are Christians who calmly say, “I respectfully disagree with your views about homosexuality because of my religious beliefs,” and yet they are immediately labeled “bigot,” among other things, by simply stating a personal belief in non-inflammatory language. This is not a good thing.

There is at least one prominent homosexual who agrees with me about this. Lesbian activist Camille Paglia, who does not share any of the beliefs of Christians about homosexuality, said: “I think that this intolerance by gay activists toward the full spectrum of human beliefs is a sign of immaturity, juvenility,” Paglia went on to say. “This is not the mark of a true intellectual life.”

Brandon Ambrosino, a liberal writer for Time and certainly not someone who shares Robertson’s beliefs, demonstrated how an opponent of the Christian worldview can offer a civil, thoughtful response to Phil Robertson without using defensive intimidation tactics. He had this to say about the methods of some gay activists: “Why is our go-to political strategy for beating our opponents to silence them? Why do we dismiss, rather than engage them?”

He also pointed out that just because someone has a religious belief that does not support homosexuality, it does not automatically make that person a bigot. In his own words: “It’s quite possible to throw one’s political support behind traditional, heterosexual marriage, and yet not be bigoted.”

We’re losing something in society. Maybe we’ve already lost it.

We’re losing our ability to offend and be offended in a civil, conversational manner.

The ability to freely offend and be offended in a civil way is critical for the well-being of society. The experience of being offended by the ideas and beliefs of another person is an essential pillar of liberty. Sure, Phil Robertson’s free speech was not taken from him. The government did not throw him in jail, and he did not sue his employer for discrimination while he was suspended. But there are people who wish that he had been put in prison.

Once society loses its ability to be offended in a civil, constructive way, its citizens will eventually lose their freedom to offend and be offended. My hope is that America will not emulate laws like the ones in Sweden, which have condemned a pastor to prison for expressing his religious beliefs from the pulpit of his church.

In other words, the rush to silence or prosecute and imprison opponents instead of engaging them in public discourse will eventually lead to widespread tyranny.

It is a sad state we are in. No longer do people rely on vigorous intellectual discourse and public debate to settle disagreements. I think of C.S. Lewis and Owen Barfield and their lifelong feud as an example. The two men could not have disagreed more — and, as preeminent Oxford scholars, they did so publicly and often; in fact, their convictions were so different that their debates about religion and philosophy were dubbed “The Great War” by Lewis. Yet they remained close friends for 44 years and met at the same pub every week to debate their ideas. How did they do this without resorting to hand-to-hand combat or taking legal action for “hate speech?”

They understood the value of being offended.

They understood that offense in the public square creates wonderful opportunities for powerful and productive debate that sharpens the logic and wit of everyone involved. It opens the conversation. It sparks dialogue — yes, heated dialogue and often times great emotion — but dialogue that (hopefully) remains civil and focused on one purpose: the free exchange of ideas.

We cannot have the free and civil exchange of ideas without maintaining the ability to offend and be offended in a civil, constructive way.

It will eventually lead to the state-enforced practice of selective tolerance, which is an arbitrary recognition by the government of free speech rights for some beliefs but not others.

By using bullying tactics in the public square — i.e. calling anyone and everyone who disagrees with your worldview a “bigot” to intimidate and slander them — you are building a culture that no longer knows how to conduct civil, fruitful discourse. When this happens, you will eventually get selective tolerance that is enforced by the full weight of government law. What if America eventually passes “hate speech” laws that make it a crime for anyone to publicly express religious beliefs that oppose the agenda of gay activists in any way, even if it is a respectful, civil disagreement with that worldview?

Whether the problem is coming from the liberal or the conservative side of the aisle (or both), a culture that is unable to offend or be offended in civil, constructive dialogue is setting itself up for eventual tyranny.

Although it might seem like a stretch, the famous quote by Martin Niemöller does apply here. He was a Lutheran pastor in Germany during Hitler’s reign. He chose not to defend other groups targeted by the Nazis because he was not a member of those groups nor did he share their worldview. He realized his error and said the following:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me–and there was no one left to speak for me.

Something that we can all learn from Phil Robertson’s recent story is this: constructive, non-insulting public debate is always better than bullying, intimidation, name-calling, and silencing of opponents.

And, as the Lutheran pastor noted above, passively allowing other groups to be bullied away from the public square is another way of promoting a culture that no longer engages in civil debate. Of course, in his time, it was much more severe. His country had already gone past the point of no return.

I pray that we become a nation that values the free exchange of ideas and knows how to handle being offended in constructive, civil dialogue — even with such personal and emotional topics as sexuality and faith.

Otherwise our nation might become a place where freedom is determined by who you offend or not offend.

You might want to stick to music since your comparison to Martin Niemöller’s quote makes zero sense to your point. Martin was saying we should all speak out AGAINST bigoted %$#*^&%!, not selectively tolerate them. And jeezopete, Phil Robertson’s free speech rights were not violated. The government was not even involved. The First Amendment protects us from the GOVERNMENT! Speaking out against bigoted views by other citizens is also free speech!

Thanks for your comment, Debi. I revised my article and refined the point I was trying to make based on some of your points. While your “stick to music” comment wasn’t very kind, I do appreciate your feedback.