Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

When life’s sorrows bring us into shadowlands, we need the joy of Christ to restore our strength. We tap into this joy by nurturing a deeper longing for God. Shadowlands and Songs of Light: An Epic Journey into Joy and Healing takes you on a quest for joy and a life-changing longing for God.

Written by a C. S. Lewis expert and a skilled composer, the book explores 18 beloved C. S. Lewis classics, from Narnia to Mere Christianity, and 13 spiritual principles behind the art of songwriting, as seen in 13 studio albums by U2–all to answer one question: how do we experience deeper joy in our relationship with Christ during times of sorrow and trial?

Shadowlands is available to pre-order at Amazon or ChristianBooks.com. If you pre-order a copy, the author will personally email you with a thank-you note and a copy of his upcoming e-book devotional “Devotions with Tolkien,” which uses J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic “The Lord of the Rings” and Scripture. (This is all on the honor system: simply pre-order Shadowlands, and then send an email to shadowlands2016 (at) gmail (dot) com letting the author (Kevin Ott) know you’ve ordered it, and he will contact you.)

Text LIGHT to 54900 to get a preview of Shadowlands and Songs of Light.

***

Published: March 9, 2015

Updated: March 26, 2016

Parental Content Advisory section located at the end of the review.

(Note: To visit Kevin’s personal blog, go here to StabsOfJoy.com.)

[Note, May 11, 2016: I had the chance to interview Rodrigo Garcia, the director of “Last Days in the Desert.” I’ve included the podcast episode of that interview above so that you can listen to our conversation about the film after you’ve read the review below. You can also read the transcript of the interview at this article.]

[Note, May 11, 2016: I had the chance to interview Rodrigo Garcia, the director of “Last Days in the Desert.” I’ve included the podcast episode of that interview above so that you can listen to our conversation about the film after you’ve read the review below. You can also read the transcript of the interview at this article.]

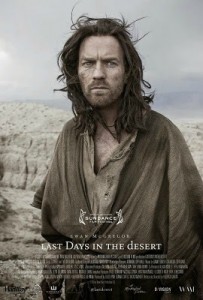

I recently [in Feb. 2015] had a very rare, one-time, “in-the-right-place-at-the-right-time” opportunity to see the new Ewan McGregor film, Last Days in the Desert

(#lastdaysinthedesert, @LastDesert), in which McGregor plays both Jesus and Satan. Award-winning director Rodrigo García (“Blue,” “Mother and Child,” “Nine Lives”) directs and writes, and Emmanuel Lubezki (#chivexp), the Oscar-winning cinematographer behind The Revenant

, Birdman

and Gravity

, is on board, besides many other talented cast and crew members.

The film, at the time of this writing, does not yet have a US release date, according to IMDB. (Though it played at the Sundance Film Festival in January.) [Update: the film will be released May 13, 2016.]

IMDB’s plot summary: “An imagined chapter from Jesus’ forty days of fasting and praying in the desert — on his way out of the wilderness, Jesus struggles with the Devil over the fate of a family in crisis.” The film uses this small fictional episode, set within Jesus’ 40 days in the desert, to contemplate the nature of father-son relationships, especially Jesus’ relationship with the Heavenly Father.

IMDB’s plot summary: “An imagined chapter from Jesus’ forty days of fasting and praying in the desert — on his way out of the wilderness, Jesus struggles with the Devil over the fate of a family in crisis.” The film uses this small fictional episode, set within Jesus’ 40 days in the desert, to contemplate the nature of father-son relationships, especially Jesus’ relationship with the Heavenly Father.

Using fiction to contemplate true events and themes is an age-old tradition, even in Christianity. I think of beloved fiction stories like The Story of the Other Wise Man by Henry van Dyke, written in 1895, which tells the story of a fourth wise man not mentioned in the Bible

— using entirely fictional events — to help readers rediscover the wonder of the birth of Jesus. That’s exactly what this film does: the fictional episode helps us rediscover the true events in the Bible and feel their emotional power. It dusts off the over-familiarity that people develop from years of reading the Gospels.

Whether or not the filmmakers intended it — and we’ll get to the whole non-religious-artists-making-movies-about-Jesus question in a moment — the film is effective in this way. And though there were a few minor moments of theological creative license (and I’ll cover those), the film stays true to the essential Christian beliefs about Jesus (the ones outlined in the Nicene Creed, for example).

The director/writer Rodrigo García said this to Christianity Today: “By choosing Jesus, I know what the end is,” he says. “I have some freedoms because [the film is] an invented chapter, but I have to obey the origin and obey the destiny.” Ewan McGregor (#mcgregor_ewan), though not religious, explained to CT that the film was made with “passion and respect.” In another interview, he said the film is “about fathers and sons. Jesus and God are the ultimate father and son relationship.” Many critics have already noted how the film contains possibly the best portrayal of Jesus’ humanity in film history. But the film did something else amazing — something I never expected.

A Stunning Analogy of When Christians Go Through “Desert Seasons”

This is what surprised me the most about “Last Days in the Desert.” The film works as a vivid analogy of something that millions of Christians have experienced: spiritual “dry seasons,” as we call them, the “desert season,” or the dark night of the soul as others call it — that parched terrain where a person who has enjoyed years of joyful fellowship with God and long, fruitful seasons of unfailing spiritual oasis — suddenly finds herself in a harsh, dry desert, a place where every attempt to draw near to God is frustrated (at least, temporarily, until the season passes). In fact, there are three stirring elements from this film that capture what the “desert season” is like.

1. A Trial of Silence; the Pain of Distance

Throughout the film, Yeshua undergoes a trial of silence and the pain of distance with the Father, in which his Father feels unusually out-of-reach. In one scene, Yeshua prays, with tears slipping from his eyes, “Father, speak to me.” The tone of his voice is not, “I’ve lost my faith.” It’s more, “My usual visibility of You has changed. Why, Father? I need You!” There’s a childlike vulnerability. He’s been out in the brutal elements for weeks, his body is worn thin, his mind is spent, it’s hard to concentrate or sleep, and he’s desperate for the nearness and guidance of his Dad.

And, I should add, this is not theologically out of line. Even if you believe that Jesus in His humanity never experienced trials of distance with God, the film’s portrayal of it works as a symbolic foreshadowing of the Cross. When Jesus died on the Cross and descended into Hell, He experienced a separation from the Father as Jesus took on the sins of the world; and He experienced this ultimate separation on our behalf so that we wouldn’t have to. In these moments when Yeshua struggles to hear his Dad’s voice, the film, also — amazingly enough — stops becoming a story about Jesus exclusively; it becomes a story about any person who has ever had a relationship with the Father.

The artistic freedom of telling an imagined chapter — not adapting an actual event from the Bible — and even the use of “Yeshua” instead of Jesus, leaves space in the story for viewers to project their own experiences into the desert panorama. The movie becomes a symbol of our own relationship with God. And like any relationship, there are ups and downs. A low period doesn’t end the relationship, it just reduces visibility for a time. And the low-visibility harshness of the desert — the fatigue, the disorientation, the merciless heat, the biting air of night — comes through so powerfully in the film (as does the breathless beauty of other-worldly desert landscapes, filmed only using natural light at the Anza-Borrego Desert state park in California), and it reminds you of all the seasons of spiritual exhaustion that ebb and flow with life.

And yet, Yeshua’s example in this movie, where he presses forward with earnestness even when his Dad’s voice isn’t clear in the desert haze, is encouraging to the heart that is intimately acquainted with the desert seasons.

Another scene stands out to me: we find Yeshua perched under a make-shift shelter, and a flimsy one that obviously came apart in the night. And the wind beats on it until its branch fragments flutter away in the wind, and his blanket is whipping like a banner — no longer covering him and completely useless. As the groggy Yeshua slowly stirs from his tortuous half-sleep, he finds numerous thistles and pieces of wood stuck all over his hair, and he has to pick them out one at a time.

And it’s frustrating.

So frustrating that Yeshua, after laughing in disbelief at his pathetic shelter, finally screams in exasperation. (Did Jesus really experience the little frustrations of life, like stubbing his toe on a rock or not getting enough sleep because the wind is too loud? You bet He did.)

So many scenes like that one capture the mini-trials of the dry season — how it’s often the little things, the small thorns of daily routines and petty problems of logistics that drive us mad when we’re going through spiritual deserts. It’s so easy to relate to when you have endured but pushed through the desert seasons. The film has many moments like this — moments when you want to point at the screen and say, “Yes! That’s exactly what it feels like. This is what the desert seasons are like. And that’s what it feels like to be distant from the Father, and you can’t figure out why.”

Of course, some might think it insane to position oneself in a similar dynamic relationship with God as Jesus experienced it. But that is not heresy. That is orthodox Christianity. In John, chapters 14-17, and in the other Gospels, Jesus explains one of the most important goals of His mission on earth: to heal the wound — the great divorce, as C.S. Lewis

might call it — between God and the human heart and give us the same close child-parent relationship with God that Jesus has. The infinite debt forgiveness of the Cross makes it possible for us to approach the perfection of God and engage the Creator in an intimate relationship. And, like any relationship, there has to be growing pains to reach new levels of intimacy.

And as McGregor’s Yeshua walks through jaw-dropping desert haunts — places more barren and beautiful than anything you could imagine (you just have to see the film to believe it) — you remember the lonely days and long nights in your own life when the usual nearness of God seemed far away, and your lips felt cracked from fatigued prayers. You feel solidarity with the Yeshua on-screen. And the gentleness and sincerity of Yeshua gazes quietly back at you — as the film’s powerful ambient desert noise captured on-location in Anza-Borrego rustles and sifts around your ears — and Yeshua says, “I understand. I know how it feels.”

2. Satan’s Assault On Our Identity in the Desert Season

Contrary to belief, the Devil is not a red-skinned imp with a pitchfork. He’s a smooth operating silver-tongued, unimaginably proud and vain illusionist who loves doing one thing above all else: assaulting the identity of those who earnestly pursue God.

And that’s another thing this movie gets right.

Ewan McGregor as Lucifer, a visual duplicate of Yeshua — except Lucifer has subtle garnishes of jewelry and vanity, and is much cleaner than Yeshua — conveys a cosmic pettiness that, more than anything, smacks of the most stubborn, stiff-necked arrogance you’ve seen. He’s incessantly irritable with a short fuse and has a shameless lust for the misery and destruction of, well, everything except himself. And everything he says — even when he seems to lay aside his hostile spirit toward Yeshua for a moment — always has this taint of, “Well, wait, is he lying again?” And then you remember, and Lucifer even agrees in one scene: he is always lying. (And, wow, McGregor’s performance — and Garcia’s writing — deserves much praise for bringing out these nuances.)

In one scene, one of Lucifer’s minions uses Yeshua’s generosity as a weapon against Yeshua and tricks Yeshua into giving away some of his water. As Yeshua realizes the scheme, he looks wearily at his water pouch, knowing that he now has less water for his journey. The analogy here? Our spiritual enemy always searches for ways to drain our mental and emotional (and physical) resources when we’re sincerely seeking God.

Another way Lucifer does this (i.e. drain our spiritual strength) is by working overtime to convince us that we’re worthless, that we have no spiritual identity in Christ, and that God does not love us. Lucifer spends much of the movie doing exactly that: trying to convince Yeshua that his Father does not love him or that his Father is not worthy of Yeshua’s devotion.

3. Yet the Desert Season Is Not All Blood and Tears

Another powerful truth that many Christians have tasted first-hand: the desert season has surprising moments of vitality — like little spots of an oasis that God provides to renew you for the remainder of the journey.

One scene in “Last Days” does this with such palpable emotion that tears still fill my eyes a little when I think of it. Yeshua, and the son from the family he meets, have gone out to fetch water for the family (Yeshua has begun assisting the family by this point), and when they reach the stream — a joyfully gurgling, shimmering stream that rushes around their dirty, tired feet — a look of such satisfaction and wonder comes on Yeshua’s face (one of McGregor’s finest moments), as the stunning desert panorama stretches behind him, that no dialogue is needed in the script. You feel the thoughts in his head: this world has such beauty, and life has such wonder and glory in it — all breathed into existence by the love and creative zeal of my Father. Such beauty in life! Such wonder! It’s no wonder that Yeshua tells the boy, at one point, “to love God above all things and love life.” And, for just a few moments — as we see Yeshua’s wonder and joy — and as that stillness lingers on-screen, you feel renewed and replenished as if you had found a stream in the desert too.

Many people have had this experience: during the driest spiritual seasons, some unexpected thing will happen that, even for just a few moments, drenches them in joy and refreshment of the heart — an unexpected phone call from an old friend, a random kindness from a stranger, or a life-giving sermon on a bright, warm Sunday morning that rejuvenates the spirit.

McGregor’s Wonderfully Endearing, Humanized Jesus

Ewan McGregor delivers what might be the most humanized, likeable Jesus I’ve seen on-screen — a Jesus who has the full range of human expression, playful spontaneity, and emotion in His personality (which is more accurate to the Bible, frankly) — without negating His divinity or His place as the only Son of God. (And, yes, the script is even careful to steer clear of the “just one among many” dilution of Jesus. Yeshua makes it clear that he is the only Son that God has.)

Yes, He is the Son of God, but sometimes we’re not comfortable with Jesus as the Son of Man — yet that is one of Jesus’ most important titles in the Bible. We can only imagine the disconnected austerity of a divine being without a shred of humanity. The fact that God baptized Jesus into the full experience of humanity’s frailty can be uncomfortable for the imagination. But when John the Baptist dunked Jesus in the Jordan River, it was a baptism of identification, and that’s the whole point of Christianity. God came here to be with us as one of us (to save us). Jesus burped. Jesus had to go to the bathroom. His clothes made him itch, and He probably scratched the itch. He had a wonderful sense of humor (after all, He created humor).

One scene in particular captures this (one among many scenes). When one of the family members farts unexpectedly, a genuinely funny moment that would make any human being laugh — no matter how mature or “grown-up” you are — Yeshua laughs too, and he laughs loudly. It’s not a peevish adolescent laugh; it’s a laugh of happy spontaneity. In this film, Jesus is someone who appreciates the comedy found in the awkward nobility that is the human body. And I believe the real Jesus was that way too during His earthly ministry.

But Wait. Is This a Faith-Based Film?

To be clear: “Last Days in the Desert” is not a faith-based film. It is not made by a religious film studio or financed by Christian companies. It is an art house film, strictly speaking; and the filmmakers have stated this. And, in interviews, both Ewan McGregor and Rodrigo García have stated that they’re not religious; though, as McGregor stated, they approached the subject with “passion and respect.” I have always believed that any artist, through the natural God-breathed gifts given to them, can create something powerful and moving that God can use to point people toward His glory and truth — whether or not that person intended it to be taken in a specific way.

A person doesn’t have to be a Christian, in other words, for God to use their work to reveal Himself and the power of the Gospel to others. Of course, because the film was never intended to be a faith-based film (i.e. a film that intentionally checks off detailed theological checklists) there are a few things that fall outside of the parameters of a typical faith-based movie — though some of them fall into theological grey areas that do not negate the essential doctrines of the faith. These grey areas, for the most part, deal with more non-essential doctrines. Here are a few examples.

1. A slightly different Lucifer than the one in the Bible.

Lucifer is portrayed as having the ability to see the future in a limited, vague way — though at one point he admits that he’s not able to do it reliably when he’s trying to decipher Yeshua’s future.

Some might feel that this gives Lucifer something close to omniscience (which is not taught in the Bible), but the film makes Lucifer limited, and even flawed in some ways, in his attempts to see the future. I think the creative license is forgivable, however, because it allows the story to develop in a certain way that I found to be very powerful. (Sorry, I hate spoilers, so I’m not giving anything away.)

Lucifer also claims to have heard every cry and seen every death on earth. If you look at how the Bible describes Lucifer, he is not omnipresent; only God sees every little detail on earth simultaneously. Ascribing omnipresence to the Devil is actually a common misconception that even many Christians make. This theological flaw is not enough, however, to outweigh the many essential truths that this movie nails with clarity.

2. The film greatly limits Yeshua’s power — though the 40 days justifies it.

Jesus does no miracles while in the desert, which, depending on your theology, may or may not be something that bothers you. I suspect they did it to emphasize the difficulty of Jesus’ 40 days — that it wasn’t just a walk in the park. The four Gospels make it clear that Jesus actually never did any miracles until after His 40 days in the desert when He “returned in the power of the Spirit,” in Luke 4:14.

3. Why the soon-to-be-famous (I’m guessing) campfire scene could inspire much debate.

While sitting at a campfire, Lucifer appears to Yeshua. The desert season has been taking a toll on Yeshua, and he is so homesick for Heaven and for the Father that he engages in a conversation with Lucifer about Heaven — just to talk with someone about Heaven and the Father.

Of course, Lucifer, the Father of Lies, obliges Yeshua and talks with lively, even passionate zeal, about the topic, but you’re never really sure that Lucifer is telling the truth. At one point, tears of sorrow well up in Lucifer’s eyes as he forces himself to remember the glory of God’s presence in the throne room. But the moment passes quickly and Lucifer pushes the emotion away and returns to his normal mode: peevishly impatient wrath and pride. And as all this happens, Yeshua looks at Satan with pity. Although I find it extremely doubtful — based on the Bible’s detailed portrait of Lucifer — that the Devil would be capable anymore of having moments of emotive, nostalgic memory of God, the film uses it as a powerful tool to highlight how desirable the presence of God is.

It’s a perfect example of art using some minor creative license (that I might not agree with in the minutia) to make a broader, more important point (that I definitely agree with!).

There are some powerful poetic passages in this campfire dialogue as well, where Lucifer explains that seeing God is like being torn apart but held together at the same time. Some folks won’t like hearing such poetic theological-isms come from the mouth of Lucifer, but you might argue that it’s generally consistent (in spirit) with the Bible: Lucifer is called the “angel of light” in the Bible (a deceiving light), and his deceptions are always cloaked with as much beauty, half-truths, and poetry as he can muster. But, in the end, Yeshua finishes the emotionally-charged campfire conversation with a simple conclusion: you fell because of your pride. Lucifer’s knee-jerk response to this statement, which you’ll just have to see for yourself in the theater, tells the audience everything it needs to know about the true nature of Lucifer. And, I have to say, I kept forgetting that it was McGregor playing both Lucifer and Yeshua — even though they’re identical physically.

Ewan McGregor as Jesus and Lucifer is a landmark performance that should go down in Hollywood’s history books as one of the best ever.

4. Lucifer’s wild quest to mess with Yeshua’s mind.

The film humanizes Lucifer in a way that might go too far for some believers — almost making Lucifer a sympathetic character in one or two scenes. But, I would say this: watch the film carefully. This film deals in nuance, and at one point, Lucifer’s character admits that everything he says is always a lie. So even in the moments when Lucifer appears to set aside his hostility with Yeshua or when Lucifer is spouting off wild claims about the Father — there’s an uneasiness to it. You’re not sure if Lucifer is genuinely stating what he believes to be true or if he is trying to mess with Yeshua’s mind.

In one scene, for example, Lucifer claims that God the Father re-creates the universe in an infinite, purposeless loop. This obviously contradicts everything the Bible teaches, and it sounds suspiciously like the oscillating universe theory, which has its origins in Eastern/New Age thought. Other moments of dialogue from Lucifer seem to suggest an underlying multiverse worldview — the belief in parallel universes — which is a modern theory in cosmology (and a weak one, in the opinion of some physicists).

So, although some moviegoers might raise their eyebrows in puzzlement at Lucifer’s bizarre claims, this actually (intentionally or unintentionally) strengthens the power of those scenes. It creates the sense that Lucifer is all over the place, grasping for straws, trying to find anything to mess with Yeshua.

On top of all that, Lucifer, in another scene, claims to see all the parallel universes, even the future of each universe, with clarity (as if he were omniscient). Yeshua doesn’t provide a rebuttal to Lucifer’s claims (which might bother some Christian moviegoers), and Lucifer is clearly trying to describe God in an insulting way; however, the context of these conversations is not a debate about cosmology. Lucifer is trying to eat away at Yeshua’s resolve to obey and believe in the Father. And he’s trying to prove to Yeshua that his Father doesn’t love him. But Yeshua, as he does in the rest of the movie, refuses to take Lucifer’s bait, which is consistent in a general way with how Jesus dealt with Satan in the Gospels.

A Deeply Felt Sorrow: The Strong Grief of Jesus

One other crucial element that needs mentioning: this film deals with an abundance of grief — often in vivid, emotional detail. Loss, death, and even views of bleak existentialism (represented by the viewpoints of the father that Yeshua meets) and even hints of pantheistic view

s about life after death (represented by the speculative viewpoints of the teenage boy that Yeshua meets) find their way into different scenes.

But Yeshua never affirms those viewpoints that clearly contradict what He would later teach in His ministry. He listens with patience and compassion, He doesn’t talk down to them, but instead He focuses on using action rather than words to communicate God’s love to the family. And when you add up all these little parts together, you see one picture in particular dominating them all: the overwhelming emotional response and tenderness that Jesus expresses as the desert family encounters great hardship and tragedy. We see a very human Jesus who feels our grief as much as we do — if not more. We see this in Scripture clearly, when, for example, Jesus weeps violently after arriving to the tomb of his friend Lazarus who has died.

It’s not a light-weight movie, in other words. It deals with some heavy themes of loss and grief, and it makes you feel these emotions deeply. I had tears in several scenes, and I was on the edge of my seat in many others as the story flirts with tragedy.

But it’s not a bad thing to feel these things in a movie — if you’re in a state of mind that can bear it — especially because these darker elements in the film highlight the inexhaustible love of Jesus and His Father.

I should also add, despite the heavy themes of this film, the marriage relationship between the husband and wife is wonderfully inspiring and beautiful: they’re intensely devoted to each other and self-sacrificing to a fault. The woman speaks supportive, tender words of life to her husband, and he risks his life to make her life better however he can. Honestly, after seeing this on-screen couple, I felt inspired to be a better husband.

The father-son relationship in the family, which really provides a heartbeat for the film, also pulls hard on the heartstrings. Anyone who has any strong emotions about their parents or children — whether positive or negative — will not walk away from this movie unscathed. It will stir deep reflection. This parent-child theme actually makes it a very accessible film. Any moviegoer, whether they’re religious or not, will find a variety of treasures to uncover and contemplate. The film has layer after layer.

One wild prediction: I can foresee some people interpreting a certain element of the father-son story as symbolic of the secular motto: “God is dead.” However, the full context of the film — and the intentions of the filmmakers as stated in interviews — rules out (in my opinion) that interpretation as something they specifically intended. The story as a whole just isn’t consistent with that idea. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention: the three actors who played the family that lives in the desert — the father (Ciarán Hinds), the mother (Ayelet Zurer), and the son (Tye Sheridan) — are phenomenal.

The Glorious Scandal of the Son of Man

Ultimately, the film provokes deep contemplation about what it means (and how wonderfully, joyfully scandalous it is) that God’s Son dove head-first into all of the filth, dung, tears, and headaches of humanity and became a person with a name and an address: Yeshua of Nazareth.

Its haunting vision of Jesus’ 40 days in the desert has stayed with me; images and sounds from the film still fill my mind’s eye in all the little moments of daily life. I walked away from the screening with my faith strengthened, my imagination baptized in desert landscapes, and my spirit refreshed. Although I couldn’t recommend this film to younger viewers (some of its mature content — much like “The Passion of the Christ” — makes it more of an adult-only film), I would recommend this film to any adult Christian in a heartbeat. You can learn more about the film at the film’s official website, its Facebook page, its Twitter page, and its Instagram page.

It released in theaters May 13, 2016.

Update: On May 12, join Ewan McGregor and filmmaker Rodrigo Garcia from cities across the US for an evening of Film + Music + Conversation hosted by Mike McHargue, Michael Gungor, Alissa Wilkinson and Gareth Higgins. For more info, please visit: goo.gl/mraiVZ

***

Parental Guidance Issues at a Glance for this PG-13 Rated Film…

5/11/16 disclaimer about my notes below: I saw an early version of this film in Feb. 2015. After seeing some of its mature content, I guessed that the film would be rated R–though I do not work for the ratings board and I have only a vague idea of what their criteria is. However, the film has been released under a PG-13 rating, and this makes me think that perhaps some of the material below (i.e. some of the nudity) has been edited to conform more to a PG-13 rating. Many readers, especially parents, like to have as much detail on the below content as possible so they can make an informed decision before bringing their family. I have not had a chance to see the final version that will be released May 13, but I will check with sources and update this section as soon as I am able to confirm the accuracy below.

The current description on Flixter.com of its rating says the following: PG-13 (for some disturbing images and brief partial nudity). This seems fairly close to my report below, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the final edit is not as graphic as what I described.

Sexual Content/Nudity: No sex scenes, but there are two scenes involving nudity. In the first, Lucifer, who has deceptively taken on the form of the mother of the family that Yeshua meets, comes to Yeshua and strips off her tunic to tempt Yeshua with lust. Yeshua resists and flees the temptation, but in the process the woman’s breasts are shown clearly. In the second scene, a man’s dead body is being stripped and cleaned in preparation for burial, and his penis and genitals are seen in the process. [My opinion about such content in a film: the depiction of nudity isn’t innately sinful; it is the context in which it takes place. In the context of these scenes, the graphic nature has a redemptive purpose — though such graphic nudity might make some moviegoers uncomfortable.]

Violence/Gore: We encounter the remains of a dead dog, and its decomposed body — mostly fur and bones — is a little graphic. In the most violent scene, a character falls from a cliff, and we see their body rolling and striking rocks. We see their body after they have landed, and their leg is graphically bent in an unnatural direction, they have bloody gashes all over their body, and the person appears to have suffered brain damage: they are staring blankly into space and repeating nonsensical syllables repeatedly until the person dies. It is a very realistic and intense scene, though it does have redemptive value in relation to the story. A man grabs his son’s throat out of rage. In another scene, we see a man being crucified, and he is very bloody, and we see huge bloody gashes on his back. He is stabbed in the side by a spear.

Language: One use of the word “hell” as in “What the ‘hell'” — used by Lucifer, perhaps the most appropriate character to use that phrase in film history.

Alcohol/Drug/Smoking Content: None.

Frightening/Intense Content: The scene where the person falls from the cliffs is very intense, emotionally painful to witness, and it leaves a disturbing feeling after watching it. The scene highlights the stark brutality of desert life, however, and it has a redemptive purpose in the story. A demon disguised as an old woman, partially reveals its demonic nature, and it is a little frightening/disturbing. A man has a dream of wolves chasing him. It’s intense, but not necessarily frightening. (It’s actually a very cool sequence, as far as the photography and composition.) The crucifixion scene is also intense (though not as prolonged or detailed as “The Passion of the Christ”).

Thanks Kevin for sharing your insights and opinions with us through this comprehensive, thoughtful and thought-provoking review. I look forward to the seeing the film.

Thanks so much, Kathryn! (And great to hear from you!)

Kevin,

This is an amazing review and has answered all of my questions plus more about what to expect from this film. As a devout Christian, I already had my heart on watching the film when it releases next month but after reading your wonderfully written review, I now know what to expect and have a broader knowledge on why the film was created the way it was. Excellent work and thank you for sharing!

Thanks so much, Christian, I really appreciate you saying that! Was encouraging to read.

Lucifer? Huh? Satan is in the Bible — this idea of something called Lucifer is only in specific translations, the biggest being the NIV.

Lucifer clearly was not in this story.

The photography of the southern california desert alone makes the film worth watching. I was prepared to dislike it because it doesn’t follow any real scripture, but it sill a very good story. All in all a film of a very beautiful area and wonderful vistas. .

Definitely agree with you, it’s not a Bible story film, and it never claims to be, but it has powerful applicability to Christian principles and its visuals are definitely worth the ticket price alone. It really feels like you’ve been transported on a journey to a far-off desert in the midst of this story. Great comment, thanks.

Finally got to see Ewan’s “Last Days in the Desert”. I really enjoyed it; however, was VERY disappointed in the ending. WHERE WAS THE SCENE OF JESUS’S RESURECTION!!!