[Parent’s Content Advisory at bottom of review.]

One of the most shocking claims of Christianity is that the Creator of the universe has loved his creatures with such intensity that he became one of them.

But it was not just a rescue operation. He did not become one of them just to save them from the spiritual darkness they have ingested or fight off the forces of “spiritual wickedness in high places” (Eph. 6:12) who have quietly (and not so quietly) enslaved them–though he did do all of those things for anyone who is willing to receive him–but he also became one of them for another reason: to demonstrate a profound empathy, to experience their hurts and pleasures alongside them, from the smallest daily nuances of life to the biggest traumas or tortures–even crucifixion.

The Young Messiah–based on Ann Rice’s novel

Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt–captures this shocking, mind-bending aspect of the Gospel better than any Jesus movie I’ve seen. I came to tears more than once, especially in the scene where Cleopas, played by

Christian McKay, receives a prayer and a blessing from the young Jesus in the Jordan River, and the scene where Severus, played by

Sean Bean, confronts the young Jesus in the temple.

As the boy Jesus (played by

Adam Greaves-Neal) ponders why his Father brought him into the world, he concludes that his childhood and his early years of growth and ordinary living are not meant for miracles and great displays of power: “I think I’m here just to be alive, to see it, hear it, feel it, all of it, even when it hurts,” as he says in one scene. The film’s final conclusion agrees with the New Testament, which does not say that Jesus did miracles as a child, but only that he “increased in wisdom and stature, and in favor with God and men” (Luke 2:52, NKJV). Confession/disclaimer: I personally do not believe Jesus did any miracles until he was “filled with the Holy Spirit” (Luke 4:1), after his 40 days in the desert.To be clear: this film does portray Jesus doing miracles as a boy. But this is where we often misunderstand how filmmaking uses a narrative framework to convey a broader message or meaning. With so many movies, we fail to interpret individual scenes within the whole context and the final conclusions that the movie makes.

So, keeping that general “look at the context” rule in mind, while this film portrays Jesus doing miracles as a boy, it:

A) eventually concludes that miracles are not the purpose for Jesus’ childhood or the 30 years of ordinary living that preceded his ministry (and this is consistent with the heart of the Gospel, as explained above);

B) agrees that God has a specific purpose and a special time for Jesus’ eventual display of power. In one scene, Mary (played by the wonderful

Sara Lazzaro) tells young Jesus: “Keep your powers inside you until your father in heaven shows you the time to use it. He did not give you to a scribe, a rabbi, or a king, he gave you to Joseph bar Jacob and me…to raise you until that time.”

Besides all of that, “The Young Messiah” (@YoungMessiahMOV, #TheYoungMessiah) also introduces its story as an “imagined year in the life of Jesus” (or something along those lines; I’m quoting from memory). The film is not claiming that these specific events actually happened in Jesus’ life, in other words. That being said, Anne Rice’s novel researches the culture, politics, economics, and social environment of Jesus’ day with incredible accuracy, and the film reflects this intense research. It recreates the atmosphere and setting of Jesus’ day with wonderful authenticity.

This leads me to the next section of the review. How does “The Young Messiah” hold up in its entertainment value? Is it worth paying the price of admission to see or is it terribly boring and poorly made?

Entertainment Value and Film Craft: Why “The Young Messiah” is One of the Best Jesus Movies

“Risen” just recently set the bar higher for how a Jesus film can and should be approached–i.e. with as much creativity, authenticity, mature writing, skill, acting talent, and care as possible. Anything less than all of these qualities when dealing with Jesus’ life and you fall quickly into camp. Well, “The Young Messiah” is right up there with “Risen.” The only other Jesus movies that have equivalent or higher quality are “The Passion of the Christ” and “The Nativity Story.” (People forget about “The Nativity Story,” but that film was phenomenal.) I would also put “Last Days in the Desert,” which hasn’t come out yet, in there, which stars Ewan McGregor as Jesus and features the same now legendary cinematographer (Emmanuel Lubezski) who did “The Revenant,” “Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance),” and “Gravity.” (See my review for “Last Days in the Desert”

here.)

Here are five things I thought “The Young Messiah” did very well:

*It has Sean Bean in it. Enough said. Most of us have been huge fans (whether we’ve known it or not) of Sean Bean since his portrayal of Boromir in The Lord of the Rings. He’s such a fun actor to watch on-screen. He’s always convincing, and he just adds substance and weight to every scene.

*The atmosphere (and its foreshadowing to Jesus’ destiny on the cross). It is rich with authentic, believable atmosphere and societal/political detail. You feel as if you’ve stepped back in time.

*Its portrayal of “The Demon” (presumed to be Lucifer). And I credit Rory Keenan’s wonderful performance and the writers for this. I love how Keenan approaches each situation and delivers his lines, and how the script has him lingering in the background of scenes. And then there’s the stunning exchange between Jesus and Lucifer, which just gave me goosebumps. It’s a memorable moment also because it speaks the truth about Satan (according to the Bible) and shatters a mistaken assumption held by many Christians (and non-Christians) in the west: that Lucifer is not omniscient. Satan is much more limited than our cultural portrayal has let on. As the young Jesus says: “You don’t know what’s going to happen. You don’t know how it’s going to end, do you?”

*Its portrayal of Herod’s madness. The way it has Herod paranoid-delusional and even the way Jonathan Bailey walks everywhere barefoot and coils up on his throne cross-legged gives us a Herod we’ve ne

ver seen on-screen before. The character just oozes with sliminess. It’s a powerful depiction of the grossness that can come to those in power who have been corrupted by greed and various lusts–especially their lust for the greatest pleasure of all: power.

*Jesus’ well-written dialogue and thoughtfulness. The exchange between young Jesus and the blind rabbi in the temple is breathtaking.

The Redemption of Sean Bean’s Character Severus

“There’s only one miracle. Roman steel.”

That’s what Sean Bean says in response to someone mentioning the miracles of the young Jesus. Other actors might have put too much into the line and made it campy, but Sean Bean leans into it with just enough weight. He convincingly carves out the stone-cold grimness of a Roman soldier who has spent his life killing innocent people as a part of his job. The story of young Jesus is not the only compelling story arc in the film, in other words. We see the journey of a cold-hearted Roman centurion as he deals with the ghosts of his past: he was one of the soldiers who participated in the murder of all the boys under two years of age in Bethlehem decades prior. The way the film works that Bethlehem slaughter into the emotional layers of the plot was effective.

In other words, I’m wanting to know what will happen to Severus as much as I’m wanting to know what will happen to Jesus. It’s such a great juxtaposition because the two characters–a grizzled, hardened soldier and an innocent boy–stand on opposite ends of the spectrum in just about every way imaginable.

Joseph’s Redemptive Arc

Mary gets quite a bit of attention whenever the Gospel accounts are told, and Joseph is often left in the shadows. Not in this film. In “The Young Messiah,” Joseph has his own story arc of redemption. We see him fail and succeed as he works through the mind-boggling challenge of trying to be a good father to the Son of God. At first, he doesn’t know how to restrain his over-protective instincts. He wants to shield Jesus from all of the larger-than-universe questions that are beginning to descend on the boy’s keen, maturing mind. In one scene, Joseph tells his brother-in-law Cleopas. “He’s just a child.” And then Cleopas reminds and counsels the anxious Joseph, “No. I was just a child and so were you. But he…he is not just a child.”

In another superb scene, Joseph, who is still trying to find his footing as a father of a fast-maturing Jesus, says to the boy: “I know you have many questions. But you need to let them sleep, in your heart, for now…Your questions are questions for a child, but the answers to those questions are answers for a man. That’s a bridge I don’t know how to build. But God does. We must trust Him.” And Jesus responds, “I do, I trust Him for everything.”

We see all the challenges that must have overwhelmed Joseph at times, but we see Joseph work through them in a satisfying way–a way that highlights his faithfulness as a father and honors the spirit of how the Bible depicts the man who was given the task of raising God’s only Son.

When Jesus was Baptized in Our Brokenness

As I mentioned in the introduction, the scene in the River Jordan brought tears. (I’d like to watch this film again just for that scene.) In it we see the young Jesus have compassion on his uncle Cleopas, who is in terrible pain and dying from sickness. Cleopas, played with great mirth and humor by Christian McKay, is stomping around the River Jordan in a delirium, a last stand against his sickness, praising God at the top of his lungs despite his illness.

The young Jesus, to everyone’s shock and dismay (as Joseph has been working so hard to give the boy a low profile), wades into the river and prays for Cleopas. I love what Jesus says next: “Father…let us keep him, please, for as long as You will.”

Let us keep him…for as long as You will.

Something about the words and the way the young Jesus said it just struck down my guard, and I let the movie seep in at that point. After Jesus’ prayer, the boy and Cleopas are submerged in the river, and we see the currents swirling around them–a haunting visual moment.

But this scene was more than just a depiction of a miracle. It was a symbol–a sign of Jesus’s lifelong baptism of identification. His entire life was one of identifying with humanity’s brokenness–touching, hearing, tasting, seeing, and feeling every corner of that heartache and messiness. This River Jordan scene in “The Young Messiah” is foreshadowing to Jesus’ symbolic baptism as an adult. When Jesus was baptized, we sometimes forget that hundreds had already been baptized in the river before he had gotten there. Crowds had literally submerged themselves into the water, and the water was flowing to the brim with all the residue of humanity as they washed their dusty, dying bodies in it. Jesus’ willingness to be baptized in all of that was a symbol of solidarity: he was immersing himself in humanity’s bubbling cauldron of sorrow, filth, and brokenness–all the stuff we swim in every day.

He was right there in the water with us.

But, in the film, before all this weighty profundity and layered meaning becomes over-serious, Cleopas shatters it with a simple question.

“Where’s the food?”

In this way Cleopas adds a nice comedic relief to a film that works with all of its might to tackle an epic subject.

And, I’m glad to report, it succeeds in what it sets out to do.

Check out “The Young Messiah” resources for your church, school, or community here.

Content advisory for this film…

Sexual Content/Nudity/Themes of Sexuality: A woman is attacked, and it’s implied that the man intends to rape her, but the man is killed before he can do anything. In a conversation later it’s implied that the bandit had raped her previously. A somewhat scantily clad (i.e. bikini top showing cleavage) harem girl dances for the wicked Jewish king Herod.

Violence/Gore/Scary Content: Violence depicted in scenes, but no bloody gore. Hardly any blood at all, and it reminds me of the way some of the classic movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age would depict and imply the severity of something without using the visual shock of wounds and gore. A Roman soldier is stabbed with a spear. Jewish rebels are cut down with swords. A boy falls and is killed after hitting the ground. We see a dead bird on the shore. A man attacks a woman, but he is killed with a knife wound. Men are crucified alongside of the road. A Roman soldier stabs one of these crucified men with a knife to shorten his suffering, out of mercy. A Roman holds a child by the throat briefly but releases her. We see flashback of soldiers killing two-year-old boys (and younger) but without any direct shots of the killings. Instead it shows the deaths by implication: we see blood splattering, shadows of swords striking victims, etc. Though in one scene a bag with a baby is thrown to the ground. The Bethlehem flashback is probably the most intense violence even though it’s not gory. Even just the thought of such a slaughter is disturbing and heartbreaking, which makes that scene intense emotionally and psychologically.

Language: None.

Alcohol/Drug/Smoking Content: Roman soldiers drink wine.

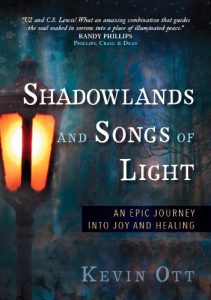

Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

My favorite jesus movie is the last temptation of christ, which you did not mention. I heard that jesus became the symbol of god becoming man, of god experiencing being a human being. we all are God’s children so we all on some level are gods experiencing being human. jesus is just the most famous one. God learns thru us all what its like to be human and live a human life.