Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

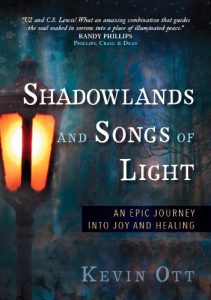

When life’s sorrows bring us into shadowlands, we need the joy of Christ to restore our strength. We tap into this joy by nurturing a deeper longing for God. Shadowlands and Songs of Light: An Epic Journey into Joy and Healing takes you on a quest for joy and a life-changing longing for God.

Written by a C. S. Lewis expert and a skilled composer, the book explores 18 beloved C. S. Lewis classics, from Narnia to Mere Christianity, and 13 spiritual principles behind the art of songwriting, as seen in 13 studio albums by U2–all to answer one question: how do we experience deeper joy in our relationship with Christ during times of sorrow and trial?

Shadowlands is available to pre-order at Amazon or ChristianBooks.com. If you pre-order a copy, the author will personally email you with a thank-you note and a copy of his upcoming e-book devotional “Devotions with Tolkien,” which uses J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic “The Lord of the Rings” and Scripture. (This is all on the honor system: simply pre-order Shadowlands, and then send an email to shadowlands2016 (at) gmail (dot) com letting the author (Kevin Ott) know you’ve ordered it, and he will contact you.)

Text LIGHT to 54900 to get a preview of Shadowlands and Songs of Light.

***

Note: Parent Content Advisory at bottom of review. Please note that though I try to do my best to keep track of every detail of the film’s content, I sometimes make mistakes (though, thankfully, it has rarely happened; I try very hard to keep the advisory sections as accurate as possible). That being said, it is understood that you are seeing the film at your own risk, regardless of my recommendation. Feel free to cross-check my content advisory with PluggedIn.com as well.

Note: Parent Content Advisory at bottom of review. Please note that though I try to do my best to keep track of every detail of the film’s content, I sometimes make mistakes (though, thankfully, it has rarely happened; I try very hard to keep the advisory sections as accurate as possible). That being said, it is understood that you are seeing the film at your own risk, regardless of my recommendation. Feel free to cross-check my content advisory with PluggedIn.com as well.

“The wind cannot defeat a tree with strong roots.”

So speaks the calming voice of the late wife of Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio), in a flashback/voiceover scene in “The Revenant,” the new film directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu that comes out Christmas Day. (#TheRevenant, @RevenantMovie, official site here)

And so speaks this breathtaking movie to its viewers — in more ways than one — as it tells a wilderness survival/revenge story set in the 1820s. Yes, it is a very brutal, realistic depiction of frontier violence, hardship, and the general wickedness of humanity. Its violence is horrific in many scenes. (Though there is certainly no “bear rape” scene, as some news sites claimed. More on that in a moment.) As far as its graphic gore, it’s up there with the WWII epic “Fury” and Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” (though not as saturated in non-stop, detailed blood and gore as “The Passion of the Christ”). But it has something else in common with those two films: “The Revenant” presents, in some ways, a generally Biblically compatible, deeply thought-provoking worldview that I found very encouraging, inspiring, and haunting to consider after I walked out of the theater.

And so speaks this breathtaking movie to its viewers — in more ways than one — as it tells a wilderness survival/revenge story set in the 1820s. Yes, it is a very brutal, realistic depiction of frontier violence, hardship, and the general wickedness of humanity. Its violence is horrific in many scenes. (Though there is certainly no “bear rape” scene, as some news sites claimed. More on that in a moment.) As far as its graphic gore, it’s up there with the WWII epic “Fury” and Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” (though not as saturated in non-stop, detailed blood and gore as “The Passion of the Christ”). But it has something else in common with those two films: “The Revenant” presents, in some ways, a generally Biblically compatible, deeply thought-provoking worldview that I found very encouraging, inspiring, and haunting to consider after I walked out of the theater.

This film stirs something deep. When I was a boy, almost every year my parents took me and my brothers backpacking deep into the wilderness of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. I can still recall what it felt like to stand there in the middle of a forest on my little grade school legs and stare at the tree line — an impossibly tall ceiling of pine tree tips that shook and shivered and scraped the sky — the thing I remember the most is the sound. There’s nothing quite like the sound of hundreds of 50-foot trees on every side of you bending, very suddenly, and swaying in a blast of wind. Those gusts from nearby summits would swoop down, and it would sound as if a giant with a 5-mile forearm was swiping his hand across the entire valley in one motion: faswooooooosh.

“The Revenant” captures that sound, and the American wilderness, gloriously. In fact, it uses the sound almost like a character theme — a motif in a symphonic score. After a wicked, ghastly murder, Hugh Glass holds the dead in his arms, and then it cuts to a shot looking up at the tree line. The wind roars through the pines. The trees bend in agony. The wind is trying to defeat Hugh Glass while his strong roots try desperately to remain in the ground — to not be uprooted and obliterated by the grief that has entered his life.

That sound of the wind in the trees tells the whole story.

And everyone who made the film must’ve known it too, especially the composers, because the soundtrack uses mostly silence, with the occasional heavy sigh of cellos and double basses, and it lets the breathing, the whispers, and the roars of the wilderness write the score.

[Need to de-stress after watching ‘The Revenant?’ Try our relaxing new guitar instrumental album Four Quiet Guitars (Vol. 1) featuring mellow guitars in harmony and other instruments–erhu violin, organ, muted trumpet, and more.]

Untrue News Headlines About the Bear Scene, Why We’re in the Golden Age of Acting, and Why Emmanuel Lubezki Rules

Three more things to tackle before I move on to the meat of my review (my analysis of the film’s themes of redemption and worldviews):

Three more things to tackle before I move on to the meat of my review (my analysis of the film’s themes of redemption and worldviews):

ONE. Some news headlines from major publications recently declared — with that loud, newsy exclaim of, GASP, controversy — that this film has a scene in which a wild grizzly bear, while attacking DiCaprio’s character Hugh Glass, actually rapes Glass.

That claim is absolutely not true. It’s laughably not true. An angry mama grizzly bear protecting her cubs tackles DiCaprio at full charge like a 440-pound linebacker, and then proceeds to maul, claw and generally Hulk-out on DiCaprio with full-blown grizzly wrath, interspersed with other realistic animal behavior — i.e. a moment where the bear stops attacking, after Glass appears to be dead, and sniffs his face curiously because it realizes Glass is not a normal kind of animal that it usually encounters. But then Glass tries to fight back, and, well, this grizzly of normal animal intelligence remembers, “Oh yeah, I was just trying to kill you because you were close to my cubs,” and then the bear just goes berserk and, well, you know, the claws come back out again, and we basically have The Passion of the DiCaprio-level carnage. (Remember when The Hulk tosses Loki around in the first Avengers movie? It’s pretty much like that but with blood everywhere.)

But there is no bear rape. Good grief, people, this is not some Southpark episode. (I’ve grown exceedingly weary of the news media these days.)

TWO. “The Revenant” has unbelievably good acting and directing. DiCaprio will likely get nominated for all sorts of shiny little statues and gizmos. Tom Hardy is, well, Tom Hardy. I read somewhere that the etymology of his last name actually comes from an Old English word that means Every Flipping Acting Role I Do Is Awesome.

This movie is more proof that we’re in the Golden Age of Acting. I’ve seen so many mind-blowing performances this year — i.e. Nelly Lenz in “Phoenix,” Saoirse Ronan in “Brooklyn,” David Oyelowo in “Captive,” Mark Rylance in “Bridge of Spies,” and the entire ensemble cast of “Spotlight,” just to name a few — that I’ve lost count. “The Revenant” just adds to the pile. It makes rituals like the Oscars feel very incomplete. There are just too many award-worthy performances and films to recognize in one dinky “award season.”

THREE. I first witnessed the work of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki after getting the very rare opportunity this year to screen “Last Days in the Desert” (starring Ewan McGregor as both Jesus and the Devil — you can read my review of it here) which won’t be released until May 2016.

Lubezki, as he did in “Last Days in the Desert,” uses only natural lighting to make the film. This is a wonderful, wonderful thing. Although, yes, “The Revenant” is exceedingly violent, brutal, and graphic at times (around the same level as “Saving Private Ryan” or “The Passion of the

Christ”), it balances the brutal R-rated realism of life in the 1820s frontier with breathtaking, absolutely beautiful shots of real mountains, forests, and plains, all bathed in natural light.

There’s more that Lubezki does that is wonderful — the long shots in the stunning action scenes and the way the camera almost works in the first-person, honing in on whoever is talking or moving and blocking any peripheral view of what’s happening around them, which adds to the suspense.

“The Revenant” has confirmed something for me: I will now, without hesitation, watch any film in which Emmanuel Lubezki is the cinematographer. I don’t care if it’s a 45-minute documentary about a half-consumed bottle of Diet Coke sitting on a suburban driveway.

I will watch it.

And, by the way, the final three seconds of “The Revenant,” a close-up shot of Hugh Glass, is among the most haunting, stick-with-you conclusions to a film I’ve ever seen. (I’m still thinking about it and trying to figure out what it means.)

Themes of Redemptions and Worldviews: ‘The Revenant’ Echoes the Wisdom of the Book of Proverbs and (Perhaps Even) Affirms the Bible’s View on Revenge

In the Hebrew Scriptures of the Bible, in Proverbs 1:17-18 (New King James Version), we read what could easily be a summary of “The Revenant.” The verse is written in the voice of a father speaking to his son, and the father warns his son about the fate of those who harm and kill innocent people for selfish gain:

In the Hebrew Scriptures of the Bible, in Proverbs 1:17-18 (New King James Version), we read what could easily be a summary of “The Revenant.” The verse is written in the voice of a father speaking to his son, and the father warns his son about the fate of those who harm and kill innocent people for selfish gain:

My son, do not walk in the way with them,

Keep your foot from their path;

For their feet run to evil,

And they make haste to shed blood.

Surely, in vain the net is spread

In the sight of any bird;

But they lie in wait for their own blood,

They lurk secretly for their own lives.

We see the truth of this proverb play out like a living parable before our eyes in “The Revenant.”

The film, almost quoting Scripture verbatim, also agrees — in a belated revelation in the hurting heart of Hugh Glass — with the Scripture’s admonition in Romans 12:19 about not taking justice into our own hands: “Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: ‘It is mine to avenge; I will repay,’ says the Lord” (New International Version).

We also see a Christ figure in Hugh Glass’s son, especially when, in a dream, Glass sees his son standing in front of a fresco of Christ on a torn down Spanish mission wall. If we really wanted to follow this symbolism, you might make the case that “The Revenant” is really a fable about God’s resurgence in the modern mind: the Hugh Glass character symbolizes God the Father, and Glass’s son symbolizes Jesus, God’s Son. Many intellectuals in the late 1800s and early 1900s were predicting that belief in God would die out on earth, and they essentially left religion for dead and assumed that belief in God had only a few short gasps of life left in human history, if that. Quite the opposite has happened. (Though that’s another article for another day.)

I realize it’s improbable that the film is actually about that (I’m drifting into movie conspiracy theory territory here) — I’m sure there are plenty of flaws in that theory above — but there is clear visual language scattered throughout the film that suggest fascinating layers of meaning.

Another very powerful theme is the “wind not defeating the strong roots of a tree” motif. It reminded me immediately of Psalm 1:3 (NKJV):

…He [the blessed man who meditates on the things that God has done and said] shall be like a tree

Planted by the rivers of water,

That brings forth its fruit in its season,

Whose leaf also shall not wither…

The film could be used as a loose, general illustration of Jesus’ parable to “build your house on the Solid Rock” and to plant your roots deep in God, as the Psalmist says above.

I also sense some very angry commentary somewhere in the film’s subtext about the injustices that have been done to Native Americans. We see either Americans or the French (it’s not clear in flashbacks) doing terrible things to Native Americans — even to the family of Hugh Glass. But we also learn that Native Americans are killing other Native Americans. And in other scenes (not flashbacks) the French kill and rape Native Americans. And the Native Americans are killing the French out of revenge. And the white men are killing each other, and those who survive are seeking revenge. Everybody is killing everybody. It’s a complicated, often contradictory and confusing mess. It reminded me, to an extent, of the complex picture painted by the recent mini-series Saints & Strangers about the first Thanksgiving and the complicated politics among the Native American tribes that shaped events.

Why Belief in Judgment Day, in an ‘Infinite Reference Point’ — Is the Only Power Big Enough to Truly End Cycles of Violence

“The Revenant” speaks implicitly about some fascinating philosophical and theological subjects. One clear observation from the film is that humanity’s need for revenge and justice is a terrifying, powerful force — as powerful as the brutal wilderness and a mountain avalanche.

In a key scene, the film makes a clear statement: there can never be enough reparations or revenge to make right those who have been wronged in the most tragic, wicked crimes. No amount of revenge will bring back those who have been lost, as John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) observes. And the film (from what I can gather) agrees on this, and it then makes its strongest point on the topic: “revenge belongs to God. Revenge is not mine,” says a character.

I bring this up to offer a criticism of a certain postmodern, relativistic thesis that says that believing in a “judgmental” God — a God who records every right and wrong and will ultimately bring every human being into the Courtroom on “Judgment Day” to examine all that he or she has said and done — makes people more judgmental themselves, and thus more aggressive and violent. It is heretical to the supposedly non-absolute dogma of our postmodern age to believe in Final Judgment or even Absolute Truth. (See my other article about Absolute Truth — that, in reality, everyone holds a set of exclusive beliefs — for more exploration of that issue.)

However, when someone sincerely, passionately, and humbly believes that God will someday make all things right and thoroughly prosecute and punish every injustice ever committed that no human power could prevent or recompense, it has the opposite effect.

The person becomes less violent and less obsessed with revenge.

Croatian philosopher Miroslav Volf, a man who witnessed firsthand unimaginable injustices and tragedies in his home country, wrote this stunning statement in his book “Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconcilia

tion” (1996):

My thesis is that the practice of non-violence requires a belief in divine vengeance. My thesis will be unpopular for many people in the West. But imagine for a moment speaking to people as I have whose cities and villages have been first plundered, then burned, then leveled to the ground, whose daughters and sisters have been raped, whose fathers and brothers have had their throats slit. Your point to them as you speak is this: “We should not retaliate.” Why not? What will ever keep them from retaliating? I say this, that the only means of prohibiting violence by us is to insist that violence is only legitimate when it comes from God. Violence thrives today, secretly nourished by the belief that God refuses to take the sword. It takes the quiet of a suburb for the birth of a thesis that human non-violence is the result of a God who refuses to judge. In a scorched land soaked in the blood of the innocent, that idea will invariably die like other pleasant captivities of the liberal mind. If God were not angry at injustice and deception and did not make a final end to violence that God would not be worthy of our worship.

He makes a slight dig at the “liberal” perspective, but, truthfully, I’ve seen the same belief — that Judgment Day is irrelevant and unreal and it’s up to us to get revenge — in the “conservative” mindset as well, though for slightly different reasons. I’m not picking a political fight, in other words. (Well, I am, I suppose, but with everybody at once.) This critique is leveled at the whole spectrum — our entire Western postmodern edifice.

In a recent news story, a father spoke about his daughter, a kindly high school teacher, who was brutally raped and murdered by one of her students. After the criminal was finally tried and sentenced to life in prison, the father said this to the press: there is no “true justice” in their current situation, despite the verdict.

The father is right.

Even if that criminal had been executed right there in the courtroom, no measure of human retribution would be enough to repay and restore all that has been lost. Such is the pricelessness of a single human life.

The idea of an eternal judgment that is made by an Ultimate Authority and that Lasts Forever is the only thing big enough to repay and restore the eternal value of a human life that is stolen from this world. Anything less is disproportionate to the value of what is lost.

In “The Revenant,” Hugh Glass’s awareness and belief in life beyond this world (through his visions of his deceased loved ones speaking to him and strengthen him) also point to the power of an “infinite reference point.” The point is implicitly made that Glass’s belief in the eternal provided fuel to endure unthinkable misery.

Another Message from ‘The Revenant’: How Suffering Tears Open the Human Soul and Exposes Its True Foundations

Viktor Frankl, an Austrian Jewish psychiatrist and neurologist who survived the concentration camps during the Holocaust, made some observations in his book “Man’s Search for Meaning” that flesh this truth out — that the belief in the eternal provides almost supernatural strength to endure the hardest of conditions. While in the camps, Frankly counseled the prisoners there.

And he began to notice a pattern: the extreme misery tore open the human soul and exposed what was really in people.

Many people who were seemingly nice people before the death camps became brutal and cruel. Others who had put all of their hopes in their careers or the happiness of their families — even the most optimistic ones — would lose hope and literally shrivel up and die. But the ones who had a “spiritually infinite reference point,” as he called it — the ones who believed there was life beyond the grave and that there was an eternal realm that was observing all that was happening in our world — were the rare souls who were able to maintain an “inner liberty,” as he called it, and retain their strong character and their buoyancy even in the most miserable conditions.

In a way “The Revenant” shows the same thing. As different characters experience miserable suffering, they react in different ways, and it brings out their true character. And constantly throughout the film, visions of Glass’s loved ones encourage him from beyond the grave, and it fuels him (along with the desperate need for revenge and justice).

Of course, I’m not saying that “The Revenant” espouses a specifically Christian depiction of the after life or even of God. But on a general level, it demonstrates the elemental truths of the principles above, and it does so in a monumentally powerful, convincing, and moving way.

Conclusion: “The Revenant,” While Certainly Worthy of Its R-Rating, is Both a Masterpiece and a Moving Film About the Priceless Value of Human Life (And My Answer to Christians Who Say, ‘How Can You Like Something Like This?!’)

My readers (many of whom are Christian) should definitely heed the Content Advisory of this film’s rating. I always say this about movies like this: parents, if a film’s rating says it’s not really for anyone under 17, please heed their recommendation.

While the gore and psychological shock value of some scenes is on par with “Saving Private Ryan” or “The Passion of the Christ” — as they unflinchingly depict the wickedness of humanity and the brutality of the wilderness with great realism — it does not glorify that wickedness. In fact, it exposes it.

Yes, this film shows us extremely grim things (as you’ll discover in the Content Advisory below). Some Christian reviewers, like PluggedIn.com’s review, found it to be needlessly graphic and grim, despite any of the positive elements of the film. And I certainly can’t blame any of them for feeling that way. I suppose I come from the Brian Godawa school of film critique — where for me it’s less about the content and more about the context and whether that context is affirming evil, making light of it, or truly exposing wickedness for its detestableness. Maybe it was also my bias toward some of the positives of the film, but I felt that the extreme grimness was counterbalanced and set in the context of a Biblically-compatible worldview. But I get PluggedIn’s point: that doesn’t mean one should necessarily always place that kind of darkness in front of their eyes.

But despite all the grimness, the thing that stuck with me the most was the haunting infinitude and sublimeness of the American frontier, as well as the sense that even one human life is worth more than we can imagine. My take is this: hidden beneath all the blood and gore, we discover a deeply moving and profound statement about the pricelessness of human life and why no recompense and retribution from the human courts of this world will ever be enough to restore what has been lost or heal the grievous wound.

We must go higher for that.

My rating for “The Revenant”: [usr 10] (See my notes below on the rating scale.)

(The “Conclusion” and the “Content Advisory” sections were revised on 12/29/15 to better explain my point of view about the film — particularly why I could affirm such a violent movie — and to clarify some of the content in the film.)

Content Advisory for Parents (or Viewers Who Want to Know What They’re Getting Into Before Seeing a Film)…

Please note that though I try to do my best to keep track of every detail of the film’s content, I sometimes make mistakes and overlook details, though thankfully these errors almost never happen. I do try very hard to

note every detail relevant to a content advisory, and I’ve been batting 1000 up until “The Revenant.” I did make an error with this film in the “Language” section (see below) and for that I apologize. That being said, it is understood that you are seeing the film at your own risk, regardless of my recommendation. Feel free to cross-check my content advisory with PluggedIn.com as well.

Violence/Gore/Scary Content: A bear mauls a man during a lengthy scene that unfolds in slow stages. His throat gets cut by the claws, and we see the claws rips portions of his back and side off — very similar in its gore to “The Passion of the Christ,” though not as intense or bloody as “The Passion.” After a man is stranded in the freezing snow, he cuts open his dead horse, removes the insides (which are shown), and he sleeps in the carcass to keep warm. It’s essentially the rated R version of Han Solo stuffing Luke Skywalker in a Tauntaun. In the opening scene, a hunting party is raided by Native Americans. We see arrows impale just about every part of a man’s body, including through his eyes. The scene begins with a naked man who has been stripped by the Native Americans and shot with an arrow wandering into camp to warn everyone in a half-lucid state. A scalping is described in frightening detail, and the aftermath of scalpings are shown on-camera. We see dozens of people shot and stabbed in the large-scale action scenes. A man’s fingers are chopped off during a fight. The aftermath of battles and raids are shown, with many dead bodies on-screen. A dead man is seen hanging from a tree. Despite everything above, the actual level of graphic gore would be about the same as war films like “Saving Private Ryan” or “Fury.” It’s extremely violent, of course, but it neither glorifies the acts of violence nor does it exceed that of other mainstream action films or “The Passion of the Christ.”

Sexual Content/Nudity: Male frontal nudity is seen briefly from a distance, though it is not detailed or very visible because of the distance, as a wounded man who has been stripped by his enemies is seen wandering into camp. A French trapper rapes a Native American woman, and the rape is depicted on-camera. PluggedIn.com summed it up well: “In a grimly gratuitous scene that is fully depicted, a Ree woman is violently raped. (Clothes don’t hide the movements, the sounds, the shame and the horror of what’s happening, and it’s implied that this is a pretty normal occurrence.)” However, the woman gets free, and she obtains a knife, and she castrates the man (though that happens off-screen, with blood shown on the man’s legs in the aftermath).

Language: There is blasphemy in this film, unfortunately. Characters use God’s name in vain on several occasions. (In the first version of my review, I had overlooked that while seeing the film. When I double-checked PluggedIn.com, they also did not mention any blasphemy. However, it appears that both reviews were incorrect. My apology for the error. This review has been corrected as of 1/27/16.) Quite a few f-words and a scattered stream of other milder swear words throughout the film. A man, the villain of the film, continues to call Native Americans “tree niggers” throughout the film.

Alcohol/Drug/Smoking Content: The mountain men and soldiers in the forts are seen drinking various forms of alcohol.

[Note: after you read my review for “The Revenant,” if you’re a fan of C.S. Lewis, please check out my new blog Stabs of Joy or my podcast Aslan’s Paw. Both seek to crack open the surprising treasures of Christian belief — the things that Western society has forgotten, ignored, or never encountered — with the help of logic, literature, film, music, and one very unsafe Lion.]

***

Note about my rating system for the movie’s film craft and entertainment value:

1 star = one of the worst movies ever made (the stuff of bad movie legends), and it usually (not always) has below 10% on Rotten Tomatoes

2-3 stars = a mostly bad movie that has a handful of nice moments; it usually falls between 10-30% on Rotten Tomatoes

4-6 stars = a decent movie with some flaws, overall. Four stars mean its flaws outweigh the good. Five stars mean equal good, equal bad. Six stars mean it’s a fairly good movie, with some great moments even, that outweigh a few flaws. A 4-6 star rating usually means it falls between 30-59% on Rotten Tomatoes (but not always).

7-9 stars = a rare rating reserved only for the best movies of that year; and a film must have a Fresh Tomato rating (60% or higher) on Rotten Tomatoes to be given 7 stars or higher, with a few exceptions (if I strongly disagree with the critics).

10 stars = one of the best films of all time, right up there with the all-time greats (i.e. Casablanca, The African Queen, Gone With the Wind, Lawrence of Arabia, Star Wars Episode IV, Indiana Jones, etc.).

So, do any of the REVENANT characters blaspheme? Take God’s name in vain?

No, not that I remember.

Watch the trailer and you will hear God’s name used in vain.

THank you for your great review. I too saw many Christian themes but only one other review expands on these and your is much better. Themes I saw included these:

Glas near dead crawling from his grave symbolic to Jesus resurrection.

Pawnee Indian who healed Glas by providing him with food, wisdom, medicine and shelter symbolic of Glas’ holy spirit who guides him out of harms way, free the Ree woman, and doesn’t murder Fitzgerald.

Glas leaping into cold, tumultuous river to escape the Ree Indians symbolic of baptism. He doesn’t drown or die but arises anew.

Glas bear attach wounds and the knife wound on his hand symbolizing the stigmata.

When Glas finally returns to the base camp near death again, the first words spoken to him were “Jesus, Jesus”.

The beautiful landscaped reminded me of Eden because man’s sin made it ugly at times.

I liked all the themes you expanded on and look forward to reading your future reviews and your writings.

Thanks very much for the kind words, Mary. Really appreciate it. You pointed out some things in the movie that I hadn’t picked up on, so it was really interesting to read your comment. It enhanced the film experience for me. Blessings to you!

Kevin Ott….I think you owe me the price of a movie ticket for may husband and me. Based on your recommendation stating there was no blasphemies – “No one takes God’s name in vain or misuses Jesus’ name” – we went to see the movie yesterday. In the first 10 minutes or so GodD…m was said 4 times and later on Jesus Christ was said twice in a blaspheme.

My apologies for the error. I double-check my notes about the language in a film with Focus on the Family (plugged in) and they didn’t mention the blasphemy. I’m sorry this was a poor recommendation.

Interesting review. Some of the scenes and content you talk about are enough to keep me home but the complexity of the material and beauty of the cinematography might draw me to see this film anyway. Also, one observation about missing teh blasphemies – usually when we don’t notice blasphemies or vulgar language, it’s because we are so used to hearing it in daily life or using it that it just passes over our heads. I have noticed that a LOT when talking to people about content in books, plays, movies, and even television shows.

Jane, you are 100 % correct! I am tired of it. As generations pass onward, profanity will only get worse unless companies start losing money by using profanity or making more money by not using profanity especially with God and Jesus’ name. Let’s stop watching and let’s get the word out to our friends etc. Ray

What you have written about The Revenant is awesome. I saw the movie and as I was watching it, Scripture kept coming to mind. When I got home, I quickly listed as many thoughts as I could…now I am matching them up with what the Bible says. The theme this month at church is connecting to God. I wish I could express myself as beautifully as you have but what I have written and will share will have to do. So happy I came across “Why I loved the Revenant”

Thanks, Mary, I was really encouraged by your comment. I’m just glad it helped someone in some way. (It was a risky movie to review for this site, and I almost didn’t do it.) Thanks again for your comment.

Hi! I’m a student at Biola University and I’m doing a cultural analysis paper on The Revenant and I’m glad I found someone who viewed this movie in a similar perspective to mine. Thank you for this article, it has helped me a ton with my essay!

I’m so glad to hear that, Cassandra! That’s really encouraging. That’s exactly the kind of thing I hoped would happen when I started doing these reviews. Thanks so much for your comment.

Ray on 9/16/16

God or Jesus’ name used in vain in movies and tv is making me crazy. It is so absolutely unnecessary and causes many people to NOT watch movies or regret them if they do!

I am fairly certain that Even a hardcore atheist would never say they would not watch a movie because it does NOT use God’s name in vain.

Kevin, that was a big mistake in your review. I know you mean well but Christians of all types need to stand up to Hollywood and start boycotting films and television programs that take our Lords name in vain!

Where can I go to try to get the word out to Hollywood? I have numerous examples where I was enjoying shows and after getting into them for 2 or 3 shows the characters start using our Lords name in vain more and more and finally my wife and I break away and stop watching. But why do the companies do it? Marvel comics Daredevil did it, Mr. Robot, Homeland, just to name a few. I am old enough to deal with gore and even other foul language but breaking a clear commandment is just wrong and unnecessary. Only the people who honor god and fill the churches every Sunday can make a difference by standing together on Christian issues.