Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

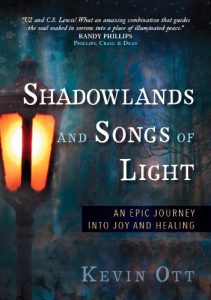

When life’s sorrows bring us into shadowlands, we need the joy of Christ to restore our strength. We tap into this joy by nurturing a deeper longing for God. Shadowlands and Songs of Light: An Epic Journey into Joy and Healing takes you on a quest for joy and a life-changing longing for God.

Written by a C. S. Lewis expert and a skilled composer, the book explores 18 beloved C. S. Lewis classics, from Narnia to Mere Christianity, and 13 spiritual principles behind the art of songwriting, as seen in 13 studio albums by U2–all to answer one question: how do we experience deeper joy in our relationship with Christ during times of sorrow and trial?

Shadowlands is available to pre-order at Amazon or ChristianBooks.com. If you pre-order a copy, the author will personally email you with a thank-you note and a copy of his upcoming e-book devotional “Devotions with Tolkien,” which uses J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic “The Lord of the Rings” and Scripture. (This is all on the honor system: simply pre-order Shadowlands, and then send an email to shadowlands2016 (at) gmail (dot) com letting the author (Kevin Ott) know you’ve ordered it, and he will contact you.)

Text LIGHT to 54900 to get a preview of Shadowlands and Songs of Light.

***

There’s a funny skit from Saturday Night Live

in which co-workers play the song “Someone Like You” by Adele

and, one by one, each person breaks down weeping. Although it pokes fun at how people interact with the song, it is also evidence of the song’s emotional power.

As a composer, I can provide one theory about why that song is such a tearjerker: it uses dissonance very well.

Dissonance in music, in this case, means the melody hits some notes that are not pleasing harmonic intervals found in the chords that are played underneath the melody. The melody causes sonic friction in your ear because the sound waves aren’t lining up with the chords in neat, easily recognizable patterns. Dissonant music simply means that two or more notes are combining to create complex wave patterns.

And the brain is not down with that. It likes simple sound wave patterns.

Adele hits quite a few of these dissonant notes, sometimes on the downbeat of the rhythm (the part of the beat that makes your toe tap), but then she quickly moves away from the dissonant note and seeks shelter in a consonant note. This quick striking of dissonance on the downbeat followed by resolution is called an appoggiatura.

Adele’s singing style really leans on these appoggiaturas to create a sudden spike of tension in the music; and then as she resolves the note into consonance, the tension is released. You feel this especially in the chorus of her song when most people begin to feel tears gathering in their eyes.

Although some composers might not share this point of view, it’s my opinion that the dissonance that we hear in pop music—like with Adele—is simply a small advertisement for a much larger, heretofore unexplored world in worship and CCM: the world of polychords.

A polychord means you stack two chords on top of each other. It’s as simple as that. Yet when you do so, it creates incredibly complex sound wave patterns — i.e. dissonance — depending on which chords you stack together. The technique has been used extensively in 20th century compositions, jazz, and various avant-garde realms of modern music. It’s not Top 40

, in other words.

Although polychords rarely have an appearance in commercial music, we flirt with them in our occasional use of dissonance. However, if constructed with great care and taste, I believe polychords could add a beautiful depth to Christian music. I believe there are brave songwriters out there who will venture more into polychordal territory to make their chord progressions more creative.

Here are two quick examples of some ways that we can borrow from the world of polychords without departing too far from the general framework of modern worship:

For Guitar

If you’re a singer-songwriter who usually writes your worship songs on a guitar, learn to play chord stacks (polychords) on your guitar, and then play around with them in your song development. The G major/D major polychord is a very easy one to learn and play, and yet it is haunting and beautiful. You simply add an open D Major chord to the bottom fingering of a G Major chord. Click here to watch a YouTube demonstration of how to do it.

If you notate polychords in your worship lead sheets instead of writing a slanted line in between two chord symbols you would stack the two symbols vertically and separate them with a horizontal line. For a full explanation with diagrams, click here.

For a Band

If you’re writing for a whole band and you’re arranging several instruments, you can divvy up the notes of polychord stacking between players. For example, a rhythm player (piano, keyboard, guitar) could lay down the first two notes of a G major chord, a G and B, as a sustaining pad or a driving rhythm. The bass guitar can stay on the root note G. Meanwhile, one or two other musicians can play the following full triad chords, one per measure: Am, G, F, Em.

These four chords will be played over the G major chord, which can be called our pedal chord for reference. The second and fourth stacked chords (G and Em) cause little or no dissonance with the pedal chord. However, chords one (Am) and three (F) have no notes in common with the pedal chord and will cause much dissonance.

You can listen to a full band doing this here. A jazz organ is playing the pedal chord, G major. Notice that the higher stacked chords (Am, G, F, Em) can be heard on more than one instrument and in different octaves. This spreads the love a little and adds depth to the harmonic landscape.

And, in those dissonant stacked chords in the odd numbered measures, you can really feel the dissonance in your ear. For me, that dissonance grabs my attention. It’s like musical espresso. It’s a little bitter but it wakes me up.

Of course, the polychordal effect is restrained a bit by having consonant chords on the even numbered measures. Each measure switches back and forth between dissonance and consonance to relieve the tension. This just eases the ear into it, especially for audiences unaccustomed to it. Also, using one long sustained pedal chord isn’t the only way to introduce polychords, but it’s an easy place to start.

For Part One Of This Article – Tips for Creative Chord Progressions in Worship – Click Here

Trackbacks/Pingbacks