Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

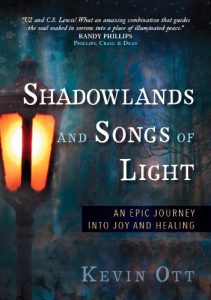

When life’s sorrows bring us into shadowlands, we need the joy of Christ to restore our strength. We tap into this joy by nurturing a deeper longing for God. Shadowlands and Songs of Light: An Epic Journey into Joy and Healing takes you on a quest for joy and a life-changing longing for God.

Written by a C. S. Lewis expert and a skilled composer, the book explores 18 beloved C. S. Lewis classics, from Narnia to Mere Christianity, and 13 spiritual principles behind the art of songwriting, as seen in 13 studio albums by U2–all to answer one question: how do we experience deeper joy in our relationship with Christ during times of sorrow and trial?

Shadowlands is available to pre-order at Amazon or ChristianBooks.com. If you pre-order a copy, the author will personally email you with a thank-you note and a copy of his upcoming e-book devotional “Devotions with Tolkien,” which uses J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic “The Lord of the Rings” and Scripture. (This is all on the honor system: simply pre-order Shadowlands, and then send an email to shadowlands2016 (at) gmail (dot) com letting the author (Kevin Ott) know you’ve ordered it, and he will contact you.)

Text LIGHT to 54900 to get a preview of Shadowlands and Songs of Light.

***

Alright, folks. I’m just going to say it.

We have a chord problem.

We need to push the creative bounds of our chord progressions in worship music

. In fact, this applies to the Christian music industry in general.

To be clear, this article series is a pep talk for me too. I get stuck in chord progression ruts all the time, and I have a bad habit of settling into comfortable routines, whether in songwriting or in live worship services. Yet when I realize the problem and go out of my way to try something risky and new, it leads to real growth as a musician.

The goal of this series of articles is not to present some perfectly comprehensive treatment of the topic of chords, but it will give you some ideas to explore when you’re writing a new worship song or playing in a worship service.

The Art of Cadence

In the classic hymn Amazing Grace you can hear the melody resolve on what’s called a “perfect authentic cadence” at the end of each lyrical phrase—or, as I like to call it, a perfect AWESOME cadence. A cadence, in short, is when the music expresses a powerful sense of harmonic resolution—a release of tension—like a sigh of relief you breathe when you finish a tough job. Music theorists came up with the word “cadence” to refer to these moments. More specifically, a perfect authentic cadence happens when you go from a five chord to a one chord.

For example, in Amazing Grace, at the end of the first stanza, you hear a chord change on the word “now” in the line “Was blind, but now I see,” and it resolves into another chord on “see,” and you feel that musical sigh of relief. That was a five chord moving to a one chord—a perfect AWESOME cadence. If the key is D major, for example, it’s an A major chord (the fifth chord in the D major scale) going to a D major chord (the first chord in the D major scale).

Every worship song ever written has this cadence or something close to it. All of Western music relies on this pleasing tension-release phenomenon—from Mozart to Rihanna

.

However, instead of always doing this predictable five to one chord resolution, try these chord substitutions to spice things up:

The Decepticon Cadence: In music theory, this is actually called a deceptive cadence; but my enjoyment of Transformers in general made it impossible not to change its name to “The Decepticon Cadence.” Composers named it “deceptive” because it sets the listener up to expect a normal V-I resolution, but then it takes a sudden twist into the minor realm by playing a V-vi combination. If you used the song Amazing Grace as the guinea pig, instead of playing the D major chord on the word “see” in that first stanza, you would play a B minor, which is the sixth chord (symbol “vi”) in the D major key (i.e. B is six notes up from D).

You can hear an example of me playing this Decepticon Cadence in Amazing Grace here.

When you’re writing a song, this is an interesting way to take the music in an unexpected direction just as you begin to hear the tension-release of a cadence coming, usually at the end of a lyrical or melodic idea.

You can also use this deceptive cadence to alter popular songs you play in the worship service and add a new twist to them.

2. The Jazz Hands Cadence: Yes, this is another name I invented, but, hey, it makes it easy to remember. This next twist on cadences hails from the jazz world. It’s a fun and easy trick to remember, whether you’re writing a new song, arranging an old one, or leading worship from your acoustic guitar or solo piano and want to freshen up your chord progression.

Similar to the Decepticon Cadence, instead of doing the typical V-I combo, you go from V to VIb7, and then to the one chord. In Amazing Grace, for example, at the end of each stanza, instead of going from A major to D major, you would go from A major to Bb7 to D major.

To hear what this cadence sounds like, click here.

This cadence works particularly well for faster songs.

The Half-Diminished Cadence: For some reason, the sound of this altered cadence reminds me of someone lost in thought, pondering a difficult or wonderful idea. It adds an unexpected, melancholic depth to the music, and it encourages contemplation among those who hear it. It works particularly well for slow songs.

To execute this cadence, you throw out the V chord altogether. So, once again using Amazing Grace as our guinea pig, instead of playing A major in the cadence at the end of each stanza, you would play a half-diminished seventh chord (m7b5). To see a chord-fingering chart for the m7b5 shape, click here.

The most common use of this cadence is with the vii chord (or seven chord). For example, in D major, the seventh note in the scale would be a C#, so the cadence progression would be C#m7b5 to D major.

However, there’s yet another half-diminished cadence that I like even more. I stumbled across it while playing 1950s bossa nova jazz. Of course, that is not the only place it is found, but whenever I play this chord, I hear the haunting Brazilian guitar of Gil Gilberto and the quiet voice of his wife Astrud

. It still uses the m7b5 shape, but instead of the “vii” chord (C# in the key of D major), it uses a flatted “ii” chord—the Ebm7b5 (chord fingering here). In this cadence, you would therefore toss out the A major chord and instead play Ebm7b5 to D major.

And, believe it or not, I tried this unusual second cadence in Amazing Grace and recorded it for you. Go here to check it out.

Using this classic hymn that everyone knows was just for demonstration. Try using these cadences in a wide variety of songs and styles; you’ll be surprised what you find.

Also keep in mind that my examples above in D major can be transferred into any key by identifying the one chord and the five chord of that particular key. In C major, for example, the one chord would be C, and the five chord would be G (five notes up from one).

In Part II of this series, looks at the incredibly wild world of polychords. Although the idea of polychords in worship or CCM might be somewhat radical, if the technique is approached with care and creativity, musicians and songwriters can do some amazing things without taking the attention away from the true focal point of worship: our Abba Father.

thanks alot and may the lord bless you.

Thanks so much, Ernest! Blessings to you as well.

I tried it,works perfectly.God bless you

Awesome! Glad it helped