Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

Quick note for fans of C. S. Lewis and/or U2 before the article begins:

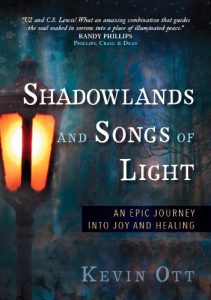

When life’s sorrows bring us into shadowlands, we need the joy of Christ to restore our strength. We tap into this joy by nurturing a deeper longing for God. Shadowlands and Songs of Light: An Epic Journey into Joy and Healing takes you on a quest for joy and a life-changing longing for God.

Written by a C. S. Lewis expert and a skilled composer, the book explores 18 beloved C. S. Lewis classics, from Narnia to Mere Christianity, and 13 spiritual principles behind the art of songwriting, as seen in 13 studio albums by U2–all to answer one question: how do we experience deeper joy in our relationship with Christ during times of sorrow and trial?

Shadowlands is available to pre-order at Amazon or ChristianBooks.com. If you pre-order a copy, the author will personally email you with a thank-you note and a copy of his upcoming e-book devotional “Devotions with Tolkien,” which uses J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic “The Lord of the Rings” and Scripture. (This is all on the honor system: simply pre-order Shadowlands, and then send an email to shadowlands2016 (at) gmail (dot) com letting the author (Kevin Ott) know you’ve ordered it, and he will contact you.)

Text LIGHT to 54900 to get a preview of Shadowlands and Songs of Light.

***

When we hear a song on the radio, we often listen to the lyrics and feel encouraged by the truths stated plainly or perhaps poetically through the English language.

When we hear a song on the radio, we often listen to the lyrics and feel encouraged by the truths stated plainly or perhaps poetically through the English language.

But how often do we listen to the musical language itself — the notes, the chords, etc. — and seek meaning there?

Did you know that the music theory — the chords, notes, and structure of the sounds — have profound influence over both our cognitive and emotional patterns? They convey meaning to us, whether we consciously acknowledge it or not.

After studying music theory intensely for my degree in music composition, I can say this confidently: the physics of sound can indeed carry messages and powerful propositions of truth to us as plainly as the lyrics. Music is just as much a language as the words we speak.

“One” by U2

I’ll show you an example. You have probably heard the song “One” by U2, one of the most famous rock songs in music history.

Here’s what U2 has told us plainly about this song’s meaning, through interviews and through the lyrics and other basic facts:

1) It’s not a blissful, peachy love song. As Bono has clarified over the years, it’s actually about breakup. (But it has to be the most beautiful, heart-rending, inspiring song about breakup ever written.)

2) The lyrics develop like a conversation between a man and a woman, though we only hear one side of the conversation. It feels like a plea or perhaps a melancholy surrender — a man realizing that the relationship is lost, and so he is speaking his final words on the subject with a conflicting mix of sadness, persistent love for the woman, anger, desperation, and a longing for the ideal of being “one flesh” with the other person but realizing how far short they’ve fallen. The anthemic chorus “one love” is spoken with sadness and irony. Something like, “We are one flesh, yet somehow we’ve let this disaster happen and now we’re falling apart. Why? How? What do we do now? If only we could truly be one. If only…”

3) It begins in a minor key (minor is what the West generally perceives as the “sad” chords) in the verse, and then changes to a major tonality in the chorus.

The Message Embedded in Two Chords

As mentioned in point three above, “One” begins in a minor key in the verse, and then changes to a major tonality in the chorus. Most songwriters will shrug at it. “So what. Minor to major. Been done a million times.”

True, but U2 doesn’t use just any minor to major combination. They use the relationship between something called the relative minor and major.

The relative who?

Let me explain this in more interesting terms.

If you’ve ever seen someone play the piano, it’s like a sprinter running up stadium steps step-by-step, running to the top, then running back to the bottom.

As you can see in the pianists fingers running up the keys, they’re playing a certain combination of notes in order. This careful ordering of notes is crucial to music. There are different musical scales because there are different ways to organize the way you run up and down the steps.

For example, maybe the runner will — this time — run two steps, skip a step and jump to the next one, then run three steps, then make a big jump and skip two steps, and he does this same pattern again and again to challenge himself: run up the steps, skip some, run more steps, skip one, etc..

Like the runner springing up the stadium steps in different ways, some scales skip different steps in different places.

Music is like finding 12 different ways to run up the stairs during your workout.

Well, here’s something wild about music: you can have two keys that sound completely different — one is sad sounding and the other one is happy sounding — and YET THEY USE THE EXACT SAME SCALE, THE EXACT SAME NOTES.

It’s amazing: one scale can contain two completely different sounding keys. In fact, every major (“happy sounding”) key has a soulmate: a relative minor (“sad sounding”) key that shares the exact same notes as the major key. They are one and the same, yet they sound completely different.

It’s not complicated though: they sound different because they start their “sequence” in different places — like starting your stair workout in the middle of the stairs while another runner starts from the bottom. You both are running the same stairs, but you’re in different places at different times.

How the Music Theory of “One” Speaks as Loud as Its Lyrics

This is how the song “One” can have two completely different sounding parts — the verse is sadder sounding and more despondent (because it’s in a minor key, A minor), but the chorus perks up and sounds warmer, happier (because it switches to C, the relative major of A minor).

Two different sounds. The exact same scale/notes.

Two in one. Sound familiar?

They’re one, but they’re not the same. Just as Bono sings in the song, “We’re one, but we’re not the same.”

The musical language is mirroring the message in the lyrics.

Of all the musical theory choices that U2 could have made in a song about two souls who were unified as “one” but then split apart, U2 chose to use this contradictory two-in-one musical phenomenon: two different keys — one cold, one hot, one happy, one sad, one blue, one red, seemingly opposite and incompatible — yet, from a certain angle, they still share the exact same notes. In a certain sense, the two are still one.

And when you place the two of them together in one space, the song is neither sad nor happy. It is a strange mix of both — a bittersweet melancholy and nostalgic grief that sways back and forth on its heels, unsure of its direction. From an emotional viewpoint, the song feels concussed or teetering with too much conflicting emotion coming from too many directions at once.

The music theory is, without any assistance from the lyrics, telling the story of the song — the song’s conflicted, one-flesh-torn-in-two tragic tale.

It is astonishing really, that music — as in the musical language itself, the chords and the notes, without any help from lyrics — can even do this.

So if music theory can convey truths about complex themes such as love and heartbreak, certainly it can convey truths about a wide number of th

emes.

And if you’re a songwriter trying to convey powerful themes and messages with your song, I urge you to think deeper than just lyrics. How will your chords and notes convey the story of your song?

(#U2, #One, #MusicTheory, #Bono, #The Edge, #BreakUpSongs, #Love, #Romance)

Just shows that simple can be powerful! Although I found the phrasing challenging to master.

Definitely agree, I still struggle with the phrasing whenever I try to play that song. Dig your music website! Really cool.